Fridge doors - how much do they really cost? (Part 2)

Fridge doors are often promoted as a simple way for supermarkets to cut energy use: add a barrier, stop cold air escaping, and save electricity.

In reality, the picture is far more complex.

In our previous blog, we explored the efficiency claims around fridge doors. Independent research and retailer feedback show that while doors can deliver some savings, these are typically quite modest compared with the headline figures and only apply to select fridges - mostly those which aren’t shopped very frequently. Additionally, when set against modern open-cabinet technologies such as Aerofoils and night blinds, the additional benefit is often negligible or even negative.

In this article, we build on that analysis to ask whether fridge doors represent a sound investment. Using financial modelling and independent studies, we also examine the broader impacts, including operational costs, customer experience, hygiene, condensation, food waste, and sales.

NB: The two main types of doors used in grocery stores are hinged doors and sliding doors. This article is based on the hinged versions, as these are, by far, the most common type of fridge door deployed in grocery stores.

From poor investment returns to compromised hygiene: 9 impacts of fridge doors on supermarkets

The true test of fridge doors is not the upfront cost, but how they perform over time. Here we assess the full picture, from finances to operations.

#1. Return on Investment: a deep dive into the financial impact of doors

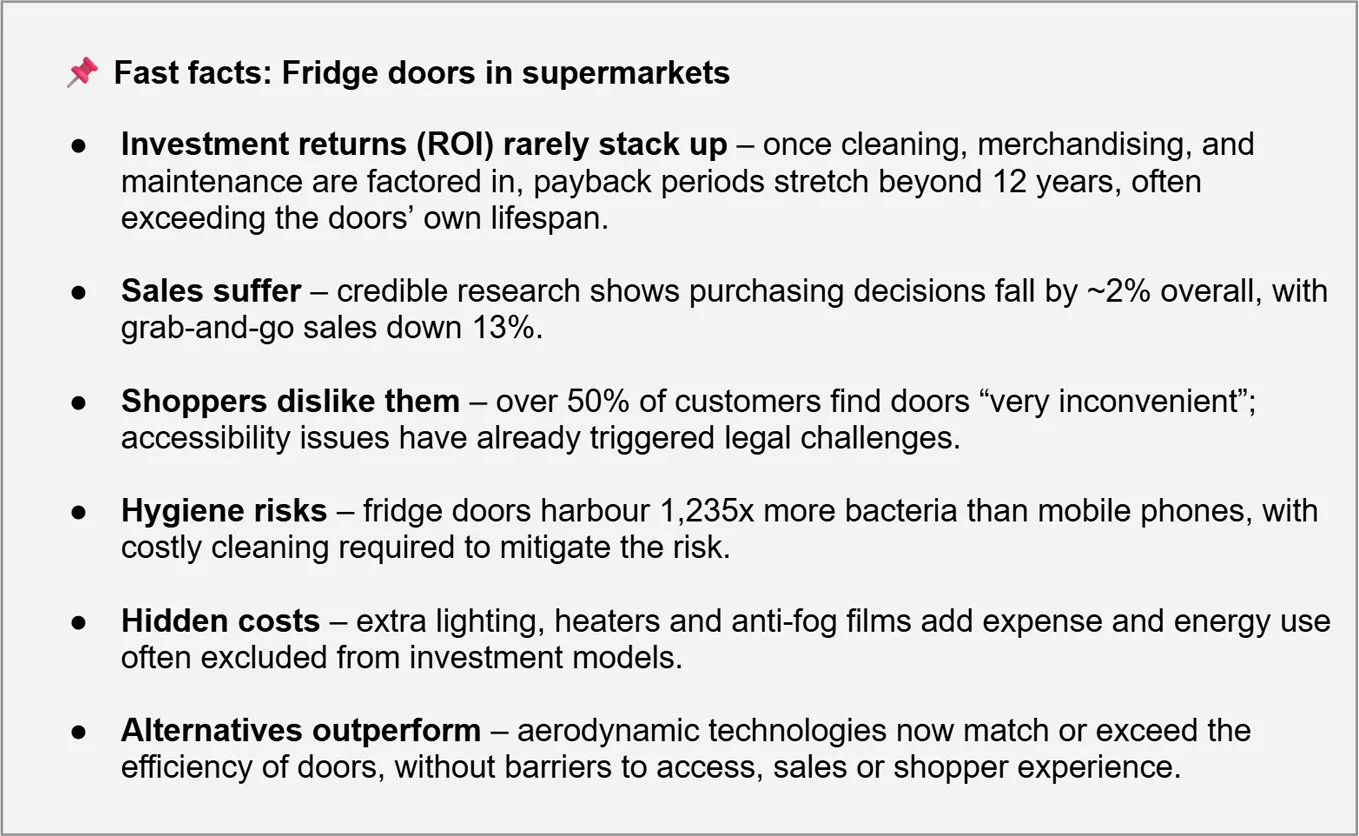

To assess the financial logic underpinning an investment in fridge doors, supermarkets should consider whole-life costs, not just the initial purchase and installation costs. At the most basic level, three additional cost categories must be included:

First, the extra labour required to keep doors clean.

Second, the effect on re-merchandising and facing-up products, since stocking trolleys cannot access the cabinets as easily, and staff are delayed by shoppers needing to open the doors.

Third, maintenance costs that arise when doors fail operationally, whether through frame movement, hinge failure, jamming, cracked or scuffed panes, or other common faults. These issues can appear early due to cabinet settlement and become more frequent as the doors age.

When these on-costs are included, the payback period on an investment in fridge doors can extend well beyond 12 years. In some cases, it exceeds the expected life of the doors, effectively rendering them a loss-making option. If a negative impact on sales is also anticipated, it is unlikely that doors will ever justify adoption on financial grounds.

With this in mind, you might be wondering, what is the investment return on supermarket fridge doors?

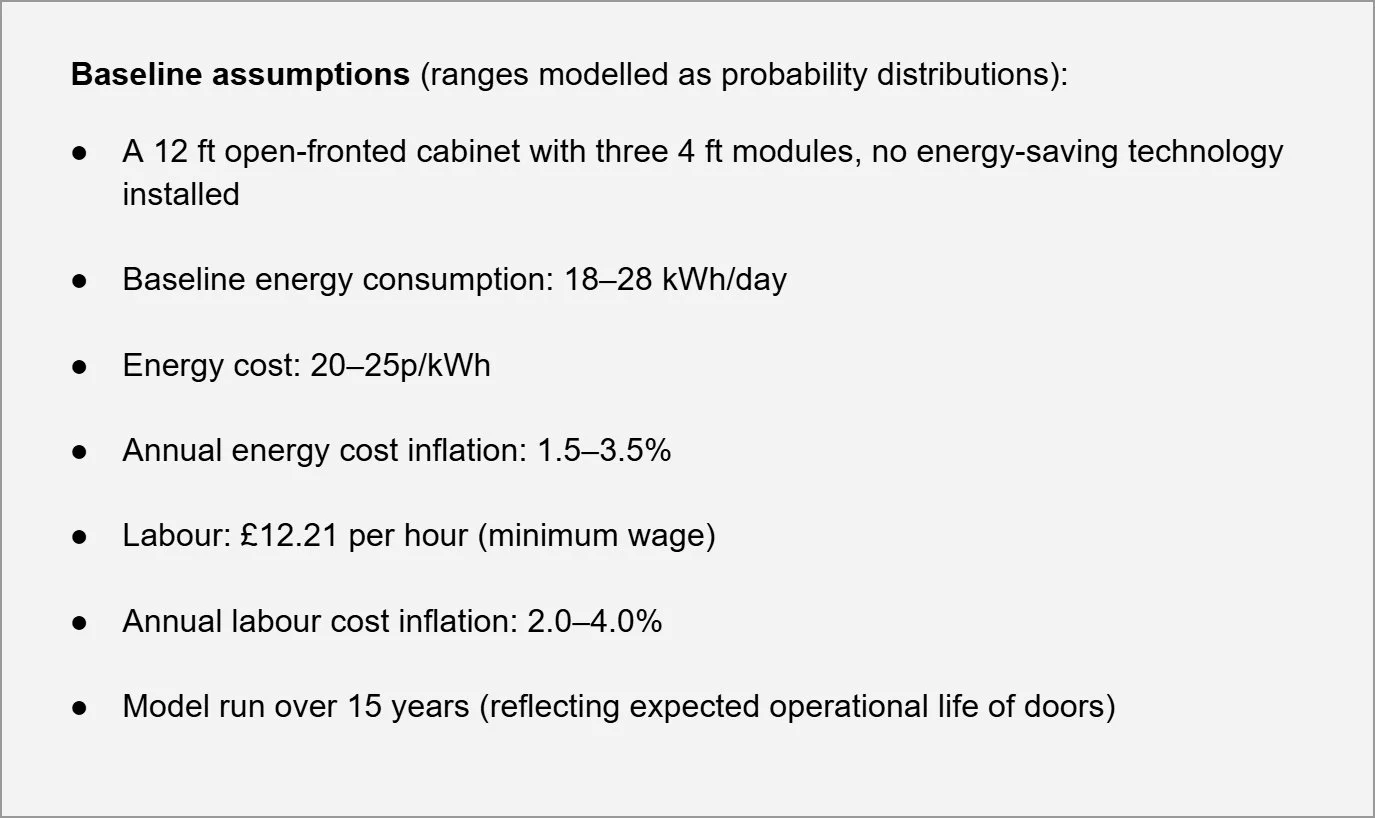

Before exploring the results, it is important to set out the baseline assumptions behind the financial model. These assumptions reflect the energy use, costs and lifespan of a typical supermarket cabinet, and provide a realistic basis for assessing the return on investment from fitting doors:

Having outlined the types of on-costs that erode the business case for fridge doors, the next step is to quantify their impact. To do this, we have modelled a representative supermarket cabinet over 15 years, using industry data on energy use, labour rates and maintenance costs. The following baseline assumptions underpin the analysis.

Investment returns (nominal terms):

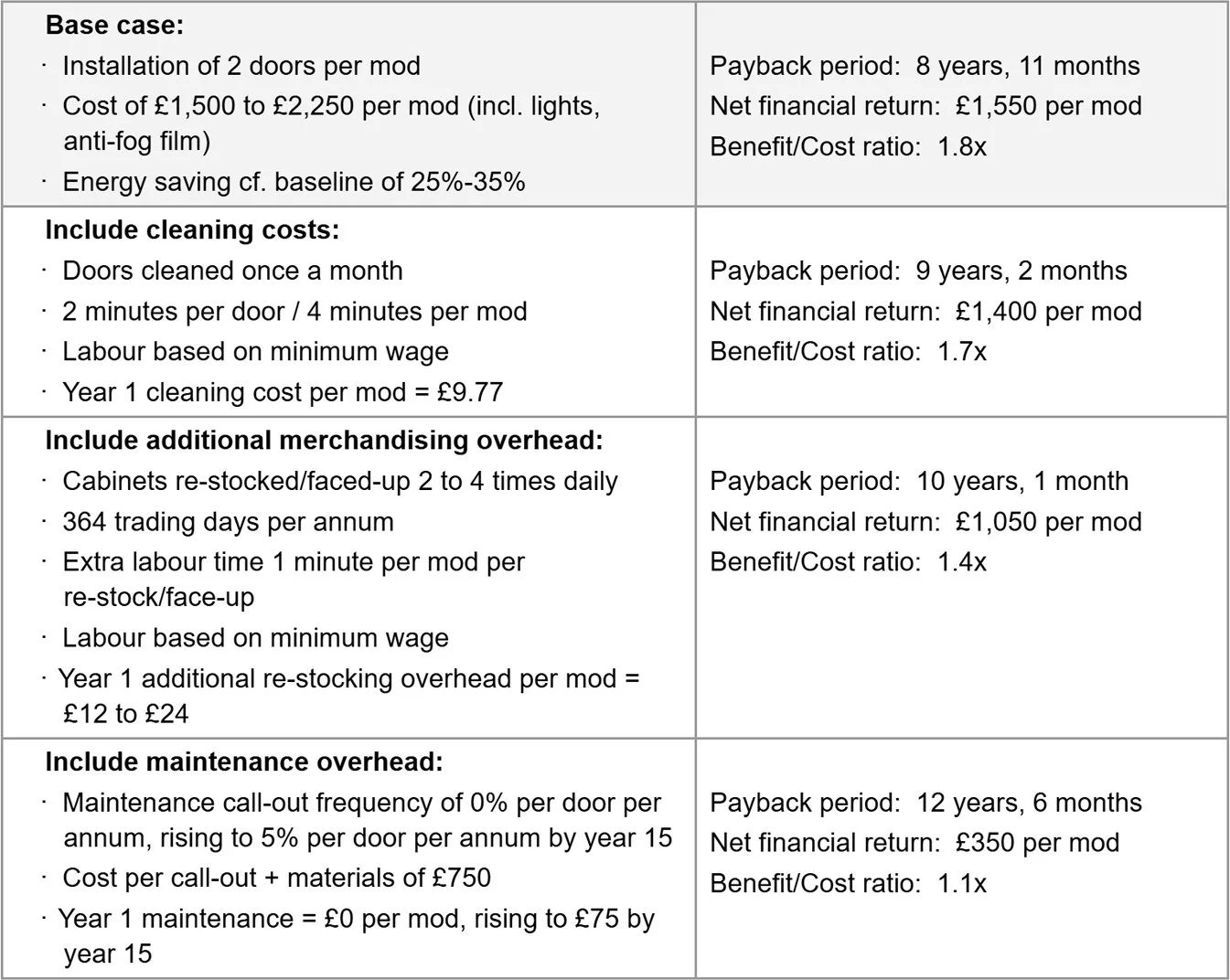

For many retailers, fridge doors represent a poor or negative investment return, a point captured in the illustration below:

Impact: significant / negative

Even when energy savings are included, the additional costs of cleaning, restocking and maintenance stretch the payback period beyond the doors’ expected lifespan. In many cases, the investment never delivers a viable return.

#2. Store operational costs

Although door operational costs are a significant burden and a frequent complaint from store staff, they are often downplayed or disregarded entirely in many financial models.

The most common issue reported by store teams is that fridge doors obstruct essential daily tasks. Restocking, re-facing products, and picking for home deliveries all take longer. At the most basic level, staff must open and prop the doors before loading stock; otherwise, the doors close on them as they work. They must also wait until shoppers have moved away before restocking, and pause if other shoppers want access to the cabinet. For home delivery picking, where speed is critical to maintaining margins, doors simply slow the process, eroding profitability.

What might appear to be a minor inconvenience becomes, over the life of a cabinet, a very real and costly burden. The reason these costs are often overlooked is that they sit within store-level operational budgets rather than capital expenditure, and so are frequently excluded from ROI calculations. In practice, however, they accumulate into a substantial expense.

A conservative example: a 12 ft fridge usually has six doors across three bays. If working around those doors adds just one minute per bay during restocking, the cost to the supermarket is as follows:

One minute of staff time costs £0.20.

With two restocks per day, that is £0.60 per day, or £216 per year, per fridge.

Over a 15-year life, this amounts to approximately £3,240 in additional restocking costs per fridge.

For a supermarket with around 50 fridges, this equates to more than £110,000 in added labour costs, excluding further delays to home delivery picking.

Impact: significant / negative

This example highlights how seemingly minor delays at store level can accumulate into six-figure costs. Yet such costs rarely appear in the business case for fridge doors, leaving decision-makers with an incomplete picture.

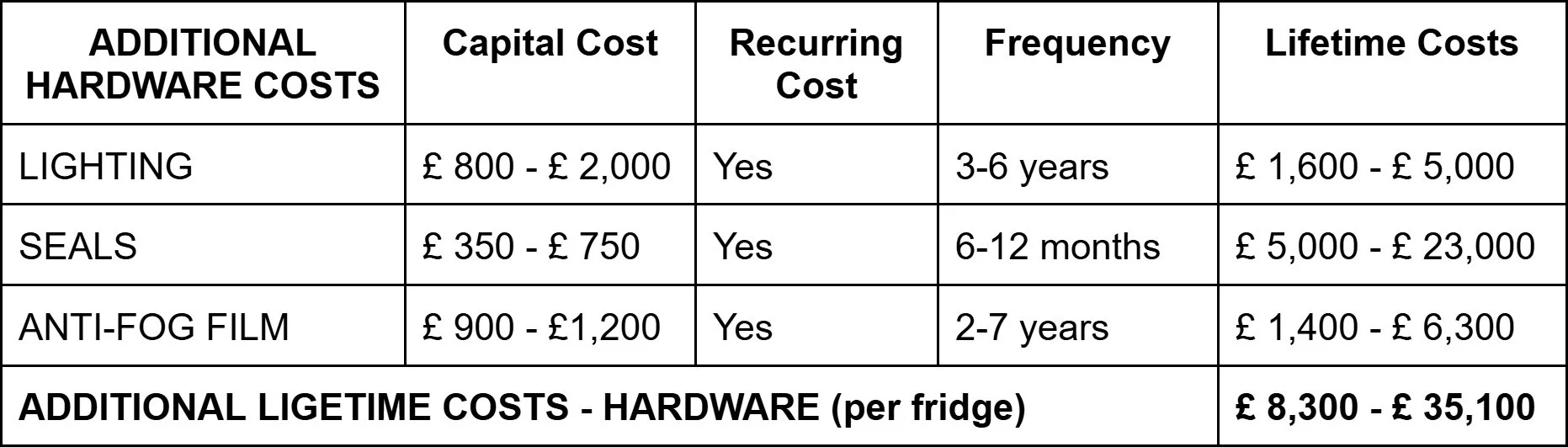

#3. Accessories – hidden extras (hardware)

Fridges with doors require significant additional hardware, adding costs which can exceed the costs of the doors themselves - yet these are often omitted from investment business cases. Some additional hardware, such as extra lighting, also consumes energy, further undermining the savings that doors are supposed to deliver.

i) Lighting

Doored fridges require far more internal lights than open cabinets, the cost of which is frequently excluded from analysis, along with the extra energy they consume. A quirk of testing, in both laboratory and stores, is that lighting energy is not measured and so not accounted for (lab tests are often without lights fitted at all, and store tests measure compressor energy, which doesn’t show the energy used by cabinet lights).

As a result, the true energy and cost impact of lighting may be entirely overlooked, where it should be deducted from claimed savings. With LED lighting typically lasting three to seven years, supermarkets may have to replace additional door lighting between 2 and 5 times over the life of a doored fridge.

ii) Door Seals / Gaskets

Doors are almost always tested in laboratories with rubber seals fitted to seal them airtight. This significantly enhances the energy savings in the laboratory, but most fridges in stores don’t have any seals on the doors, so gaps between doors are present. This is one of several causes of savings, as doors are much less in stores than in laboratory tests.

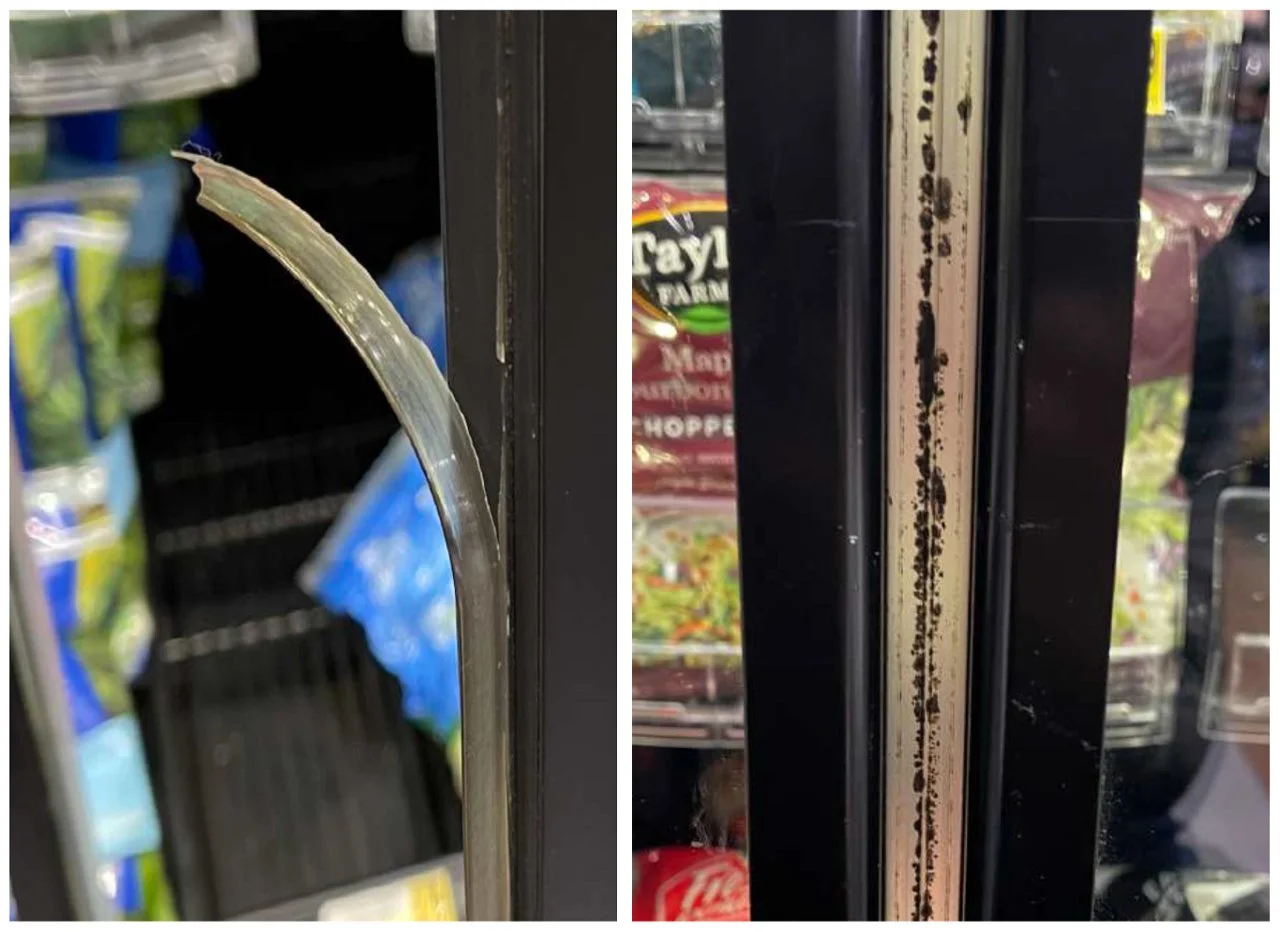

The main reasons for not using door seals in stores are i) seals are prone to frequent failure, incurring recurring costs to replace, and ii) door seals attract visible bacterial growth, which is unsightly and unhygienic.

Door seals are prone to failure and attract visible bacterial growth

Supermarkets that use door seals face ongoing costs to replace them as they fail, and to keep them clean of visible mould growth. Most stores which don’t have seals experience diminished energy savings.

iii) Anti-fog film

Most modern doors are instead fitted with anti-fog films in place of heaters, but these too represent an added cost. Cheaper hydrophobic films are prone to failure, scratches, bubbles and yellowing, requiring frequent replacement. Higher-quality films perform better and last longer, but still increase upfront costs compared to open cabinets.

Based on a single 3.75m doored fridge, with 6 hinged doors and an average cabinet life of 15 years

Impact: significant / negative

When additional hardware such as lighting, heaters and films are factored in - as both upfront capital cost, and ongoing recurring costs, the financial case for fridge doors becomes unsustainable. What is often presented as a simple retrofit quickly becomes a series of extra and ongoing costs that erode both savings and return on investment.

#4. Loss of sales - do fridge doors impact shopper behaviour?

One of the biggest concerns for supermarkets when considering fridge doors is the potential loss of sales. This is sometimes dismissed as unlikely, on the assumption that shoppers will not be deterred by the need to open a door. But is that assumption justified?

Most claims in favour of doors improving sales are anecdotal and lack credible evidence. It is not uncommon for proponents to argue that doors encourage more considered purchases, but there is little data to support this. By contrast, there is more robust research indicating that doors have a negative effect.

A 2018 study by SBXL, reported in the Cooling Post, examined the behaviour of 65,000 shoppers using in-store cameras across multiple dairy aisles, with and without doors. The findings were striking.

Shoppers fall into two distinct groups: those who read labels and those who do not.

Label readers accounted for 10% more purchase decisions than non-readers.

The presence of doors reduced the proportion of label readers from 31% to just 9%.

Assuming that inhibited label readers purchase at the same lower rate as non-readers, the study suggests that fitting doors causes a reduction in purchasing decisions of around 2%. In grocery retailing, this is highly significant.

The impact was even greater in certain categories:

New products – sales were disproportionately affected as they rely heavily on label reading.

Grab-and-go items – sales fell by 13% when doors were installed.

In summary, the study shows that fridge doors are likely to reduce purchasing decisions by around 2% overall, with certain categories experiencing much sharper declines. Importantly, the research did not identify any sales benefits from the use of doors.

Impact: significant / negative

Sales reductions of even a few percentage points can translate into major revenue losses at scale. The evidence suggests that fridge doors risk undermining trading performance, rather than supporting it.

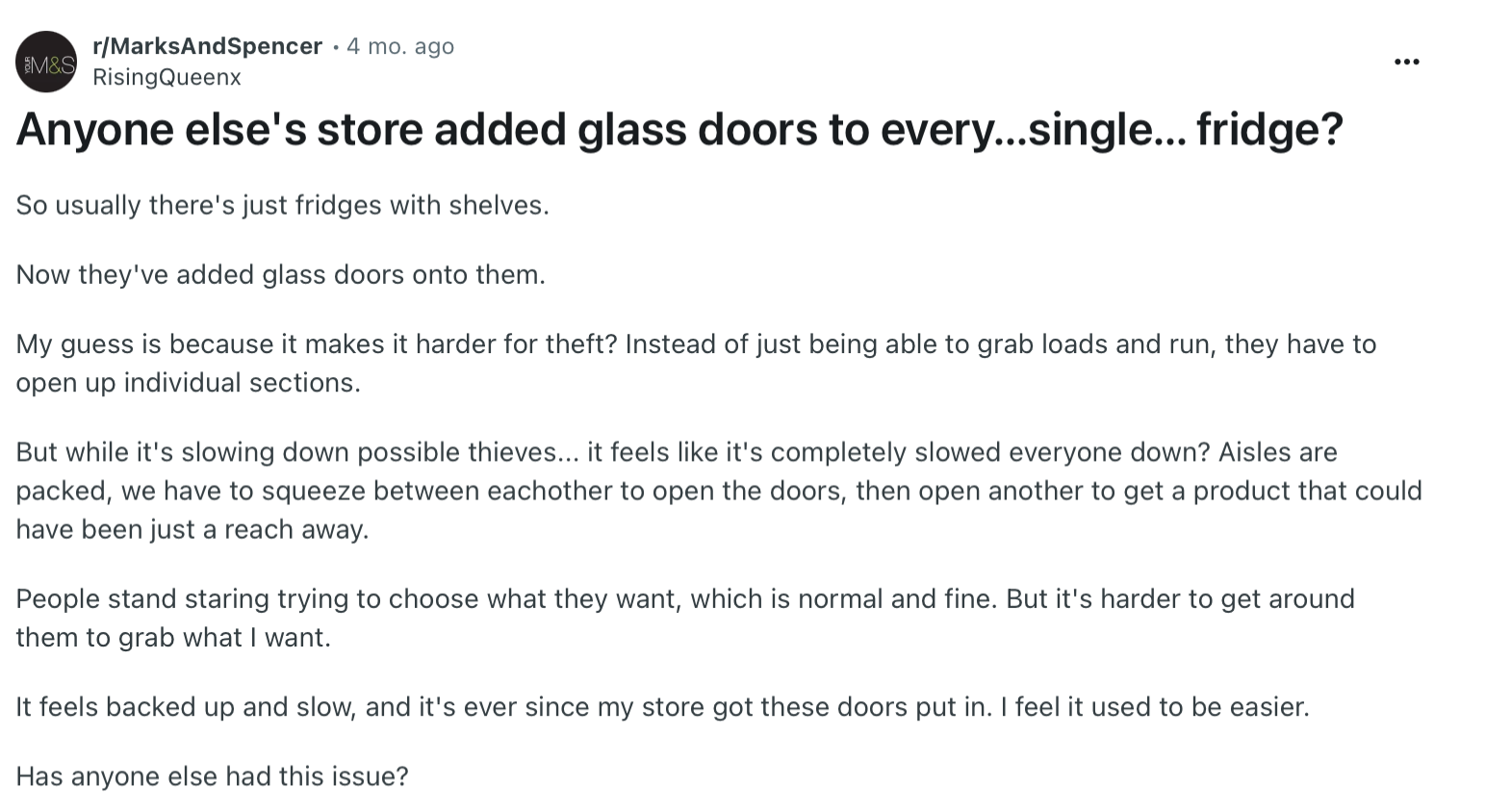

#5. The customer journey

There is limited detailed research into how fridge doors affect the customer journey. However, the existing evidence suggests a largely negative impact. For supermarkets, even a small portion of shoppers experiencing a negative impact from doors may translate into a significant impact on their business.

A 2021 paper from the University of Strathclyde, citing data from prior studies, across three leading supermarket chains, reported the following findings:

“Over half of the customers expressed that browsing products in closed cabinets would be very inconvenient.”

“They would struggle to open the doors whilst holding a shopping basket.”

“The general responses were negative towards adding doors, and issues such as condensation on the glass doors disrupting their shopping experience were raised.”

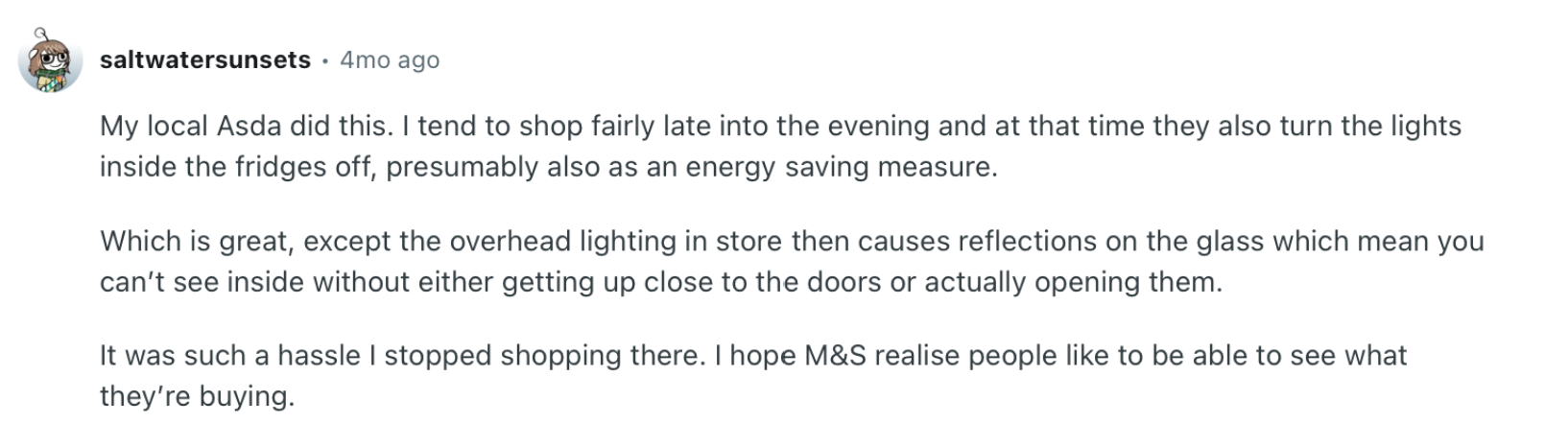

Anecdotal feedback online reflects a similar view. Internet forums frequently feature shoppers describing fridge doors as awkward or frustrating to use:

While some members of the public argue that open fridges “waste energy,” these comments often stem from domestic comparisons, inflated energy claims and a lack of understanding. There is little evidence on how widespread these views are, or how they might translate into acceptance of doors if those same people had to shop from them. What this suggests is that stores could improve communication about how supermarket refrigeration efficiency is actually achieved. There is also a tendency for unqualified observers to ridicule shoppers who complain about doors, and to castigate supermarkets who take these shoppers seriously. However, it is essential for supermarkets, which work at extreme margins in a highly competitive sector, to avoid doing anything that might cause any of their customers to abandon them in favour of one of their competitors.

For disabled, elderly and sight-impaired shoppers, the consequences of fridge doors are even more serious. In 2024, a series of news stories* accused supermarkets of discrimination after the installation of fridge doors reportedly made shopping impossible for some wheelchair users. What began as a disability advocacy publication quickly spread across mainstream outlets, including ITVX and The Telegraph, and gained traction on social media.

Impact: significant / predominantly negative

From everyday inconvenience to potential legal challenges, the evidence suggests fridge doors risk damaging the customer experience and alienating key shopper groups. What may begin as irritation for some can escalate into reputational risk for retailers.

#6. Hygiene – are fridge doors unhygienic, and what is the cost?

Mobile phones are often cited as benchmarks for bacterial contamination, given their reputation as breeding grounds for germs. But how do supermarket fridge doors compare?

A 2017 study by Reusethisbag, conducted with EMLab P&K, spent several months swabbing multiple supermarket touchpoints, including fridge doors. The results were pretty alarming:

Fridge doors harboured 1,235 times more bacteria than the surface of an average mobile phone.

Door swabs recorded 33,340 bacterial colonies per square inch, compared with just 27 colonies on the average phone.

The bacteria found were rated as “dangerous,” with gram-positive cocci, linked to strep throat, staph infections, pneumonia and even blood poisoning, among the most common.

Some of the bacteria detected were antibiotic-resistant.

The challenge for supermarkets installing fridge doors is stark: either commit to the cost of daily cleaning across every door, or accept the presence of high bacterial loads with the associated health risks. Both scenarios carry a significant cost, whether financial, reputational, or both.

Impact: negative

Hygiene concerns reinforce the wider case against fridge doors. Beyond operational inefficiency and poor customer experience, they present a tangible health risk that is costly to control and damaging if ignored.

#7. Condensation - “I cannot even see the food”

Condensation is a universal problem for supermarkets using fridge doors, and as global climates warm, it is only likely to worsen. Even in the UK, it is now common to see doors misted over, obscuring the products behind them and frustrating shoppers.

Furthermore, condensation is often perceived as unhygienic, which can erode shopper confidence.

Two types of misting occur on fridge doors:

Inner surface condensation – forms when doors are opened. This can be reduced with anti-fog films, although the films add cost and vary in quality. Low-cost options can degrade quickly and appear yellow, scuffed and develop air bubbles. Higher-grade films such as ‘Ovaglas - Clarifoil’ perform better, but still represent an additional expense.

Outer surface condensation – forms whenever humidity is high. Unlike inner misting, this cannot adequately be prevented with films. The only way to keep the outside of doors clear would be to wipe them down every few minutes, a clearly unviable approach in trading stores.

Impact: significant / negative

Condensation undermines both the shopper experience and product visibility. For retailers, it means added costs, constant maintenance, and an unavoidable drag on sales whenever doors are misted over.

#8. Heating cost savings

One potential benefit of fridge doors is that they can reduce the need for aisle heating, improving shopper comfort and delivering some heating energy savings.

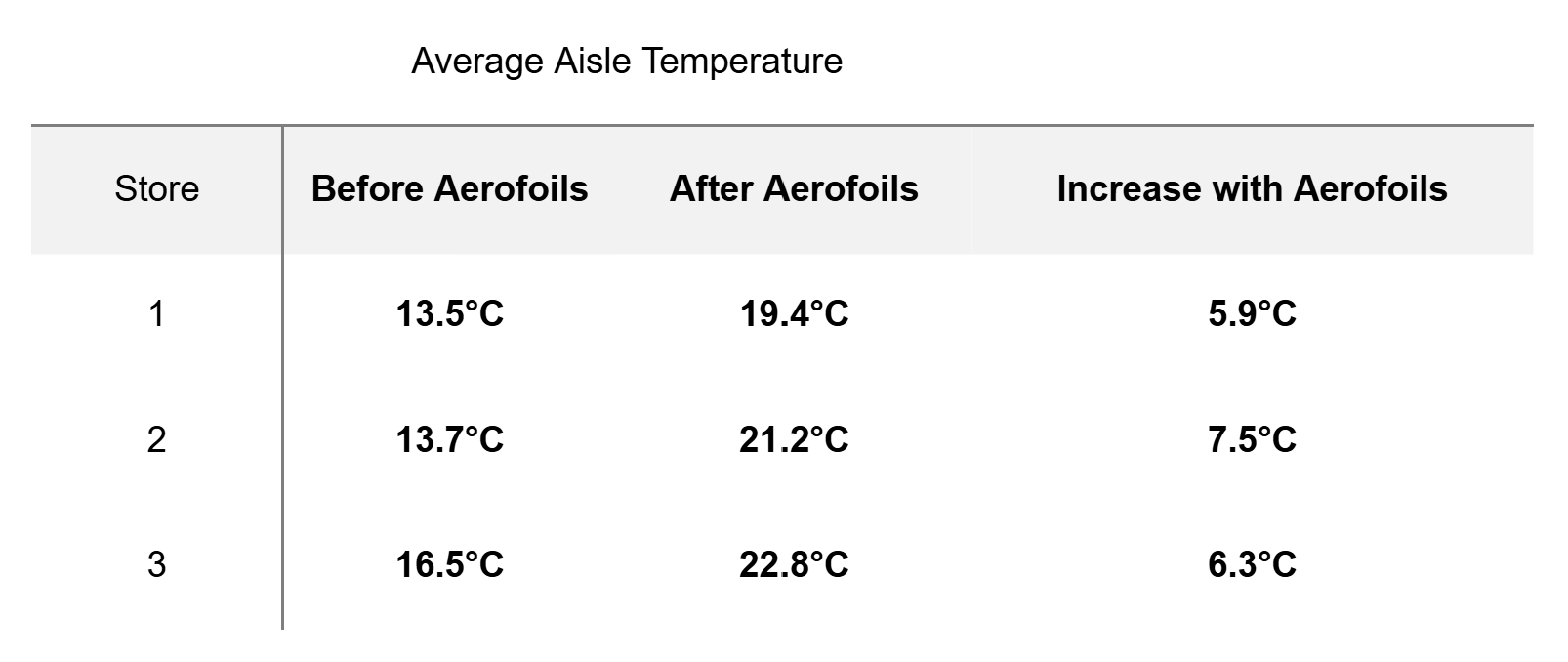

However, these savings are often overstated, since comparisons are typically made against completely open fridges with no additional supermarket energy technology. In 2016, a large supermarket group studied the effect of installing Aerofoils on open chiller cabinets. The results showed that aisle temperatures increased by an average of 6.5°C — without any additional heating.

This shows that the most relevant baseline for assessing heating savings is an open cabinet with Aerofoils, rather than an untreated open fridge.

A separate study also highlighted that perception matters as much as reality. It found that fridge colour influenced how shoppers perceived aisle comfort: customers reported feeling colder in aisles with white fridges and warmer in aisles with black fridges.

Impact: positive, but limited

While fridge doors can contribute to warmer aisles and modest heating savings, the effect is far less significant when compared against modern aerodynamic solutions. Shopper perception adds another layer of complexity that is not always captured in financial models.

#9. Cooling cost increases

The flip side to potential heating savings is the increased demand for cooling. Even in cooler regions such as the UK and Northern Europe, supermarkets rely on store-wide air conditioning during the summer months. In warmer climates, including much of the US, Asia, and Southern Europe, open fridges reduce overall cooling demand by absorbing and removing excess heat in stores, which results in less demand from air conditioning. When doors are fitted, some of this effect is lost, and this results in increasing demand for air conditioning.

It should be noted that relying on refrigeration cabinets for store cooling is far from ideal. Nevertheless, it is the reality in many trading stores, and the shift in cooling load should be factored into the total cost of fridge doors.

It is also fair to acknowledge that this drawback is not unique to doors: any technology that reduces cold air spill from open cabinets can have a similar effect - for example, Aerofoil technology has a similar impact. However, in most cases, the impact is slightly less pronounced than with doors.

Impact: negative

While fridge doors may cut heating costs in some scenarios, they often shift the burden onto air conditioning systems — creating hidden cooling costs that offset much of the apparent benefit.

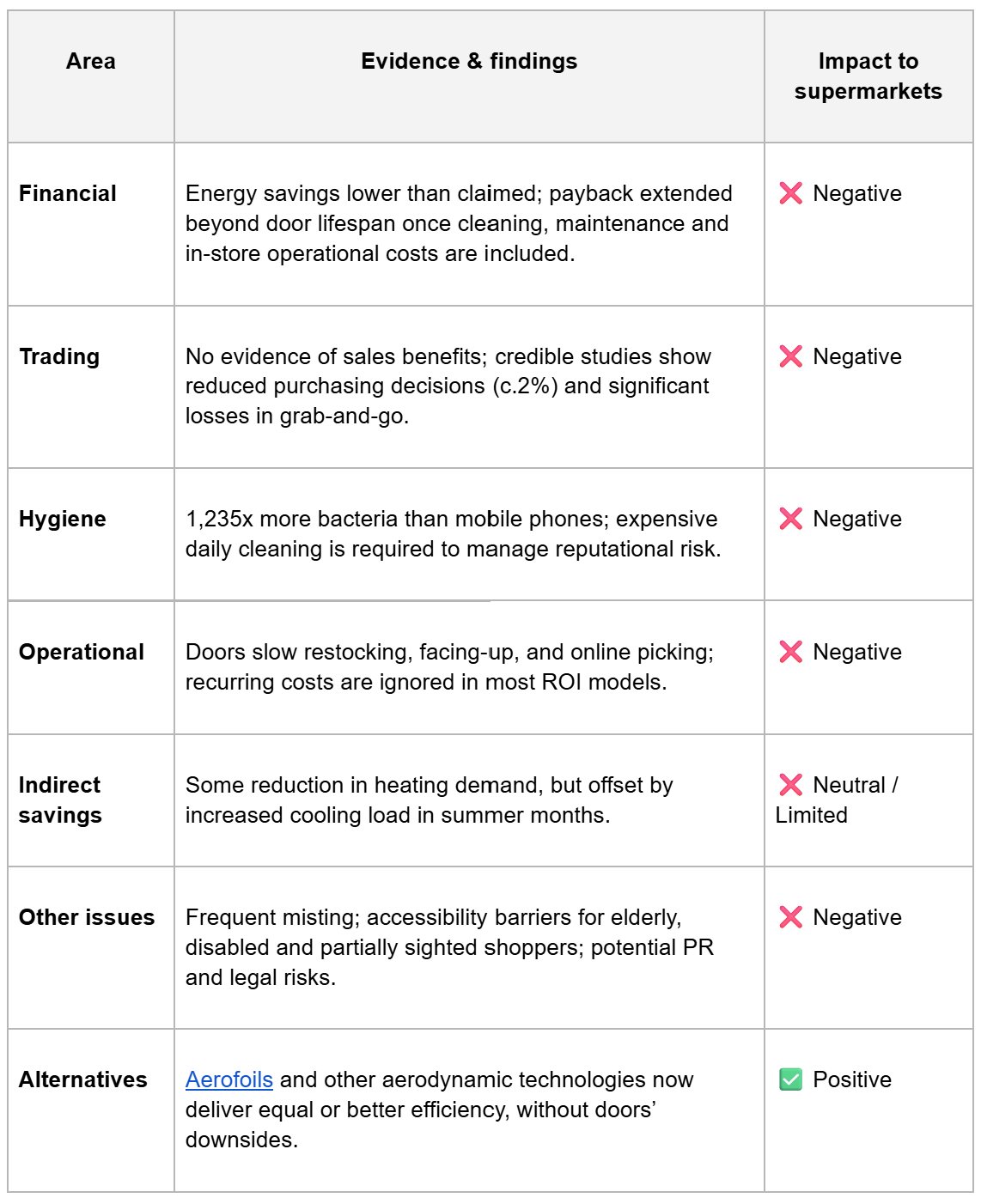

The balance sheet on fridge doors: what the evidence shows

The analysis across financial, operational, customer, and technical impacts reveals a consistent pattern. While fridge doors can deliver some energy benefits, these are quickly outweighed by hidden costs and unintended consequences. The table below summarises the evidence.

Taken together, the evidence suggests that fridge doors are a difficult investment to justify. Their promised benefits rarely materialise at scale, while their hidden costs accumulate year after year. Emerging technologies, already proven with leading retailers, now offer supermarkets the ability to achieve high efficiency without compromising shopper access, customer experience or operational simplicity.

Balancing gains with reality: the case for smarter refrigeration

Fridge doors promise savings, but the reality is less convincing. Across financial returns, operational performance, customer experience, hygiene, and sales, the drawbacks are clear and recurring. Doors may deliver modest efficiency benefits, but hidden costs, reputational risks, and lost revenue can undermine these benefits.

Retailers need solutions that deliver efficiency without compromise. With aerodynamic technologies now proven to match or exceed the efficiency of doors — and without the barriers or costs — the benchmark for refrigeration has changed.

Supermarkets that adopt these innovations can expect energy savings, improved shopper comfort, and reduced maintenance burdens, all while preserving the open and accessible formats that customers prefer.

If you are reassessing your refrigeration strategy, our team would be pleased to share the data, case studies and practical insights that leading retailers are already acting on. Get in touch with us to explore the alternatives.

* Headlines from Disability News Service, ITVX, Telegraph:

Disability News Service – Co-op faces discrimination claims over inaccessible fridges

Disability News Service – Seven supermarket chains accused of inaccessibility

Telegraph – Marks & Spencer faces legal action over eco-fridges

ITVX – Energy-efficient fridge doors ‘taking away wheelchair users’ independence’